When people ask why the group of 11 Veneto market gardener families settled on land in the 1930s in the area they used to call Lockleys on the northern side of the River Torrens, I’ve concluded that there were four main reasons.

- Their origins as contadini or peasant farmers in the Veneto region motivated them to live and work on their own land. They had all come from contadino families and were used to small-scale farming and knew how to cultivate the land

- The group recognised that it was possible and profitable to lease land in South Australia during the 1930s and the majority of the first-generation market gardeners bought their land after the war when regulations were eased

- The family work team including husband, wife and children reduced the costs of setting up the market gardens

- The contadino tradition of living in a close settlement explains the formation of an enduring community that shared the same occupation in a paese similar to a village.

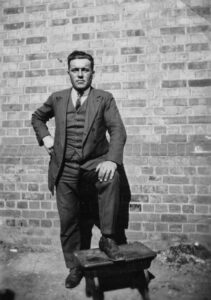

It took several years before the first generation of men could settle in Adelaide because of the difficult economic conditions during the Depression. They had to find casual work wherever they could find it – in rural South Australia or Victoria and some worked on mica mines in the Northern Territory. It was only possible to settle with their wives and children once they had a guaranteed income.

The men found land that was available to lease probably through word of mouth and the contacts made through the boarding houses in the west end of Adelaide where they stayed in the first years. I am not sure who was the first to lease land but the group gradually established themselves during the 1930s. If you’re reading this, and know when your parents or grandparents settled on their land, please contact me.

The properties were within a radius of about three kilometres, an easy bike ride or walk. The men worked hard and those who were married brought their wives and children from Italy. Some married by proxy and others married in Adelaide. By the beginning of the war in 1939, all the men who had arrived between 1926 and 1928 were married and working market gardens in the Lockleys area.

In 1935, eight years after Secondo Tonellato had arrived, his wife Elisabetta and five children joined him. the third son, Lino, was 9 years old. In his interview he reflected on his father’s early days as a market gardener at Lockleys and then refers to the context of the Veneto region which he recalled from childhood and where his father and others in the first-generation of veneti had worked as contadini …

The whole area was all market garden, you know. Well, I suppose they had to get a living somewhere … When they come here they couldn’t understand much, speak much English, didn’t know what to do, so they had to start off something because over there, they only had little gardens too, and where we come from [in the Veneto region] they used to plant once a year because you’d get the snow that high, every year, I still remember the snow there … he heard from other people, see he knew some other people that came here. He knew how warm, that you never get snow here unless you go to the mountain.

(Lino Tonellato interviewed by Madeleine Regan, 16 July 2010, JD Somerville Collection, State Library of South Australia, OH 872/10, 14).

Lino, who was eighty-four years when interviewed for this project, remembers the land in the province of Treviso in the Veneto region and his focus on climate reflects his cultivator’s knowledge of seasons. He connects ideas about land use and agricultural practices in the Veneto with the experience of the first generation and their efforts to gain a livelihood in family market gardens at Lockleys. Lino captures the narrative of the Veneto market gardeners; the initiative to preserve the contadino heritage of working the land and the adaptations and changes required to establish commercial market gardens in Australia. Through his perspective as a 1.5-generation son, Lino communicates a feeling of nostalgia for the Veneto region.

The compact area in which they lived and worked provided physical and social security and a sense of separation from the Anglo Australian world. Market gardens were divided by thick hedges of boxthorns, pine trees or bamboos along tracks which extended away from made roads.

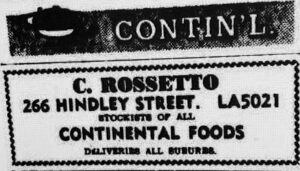

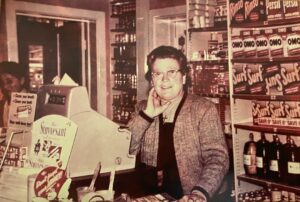

Accommodation on the landholdings varied from an early tent dwelling to a repurposed cow shed to iron and wooden shacks that could be dismantled and moved easily, to a large old colonial villa first acquired by Gino Berno during the war. In 1930 Adele (Lina) Bordin arrived to join her husband, Gelindo Rossetto and found that she was to live in primitive conditions in a tent, “a hovel – bare and empty – with no gas, no firewood, no electricity and no floor,” (Rossetto, La Pioggia nelle Scarpe, p. 68).

Ownership of land was a definite step towards permanent settlement and the formation of identity in Australia. The path to ownership was not simple or quick but the Veneto group successfully negotiated the means to work the land, and with the assistance of the family labour unit reached the goal of becoming self-employed market gardeners in the 1930s, and landowners by the mid-1950s.

Madeleine Regan

19 June 2021