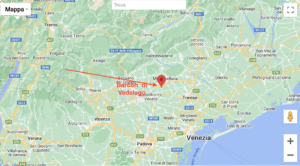

In this blog, Diana Panazzolo nee Santin writes about the Veneto food traditions that have been passed down to her from her mother and grandmothers and which she is passing onto her daughter and granddaughters.

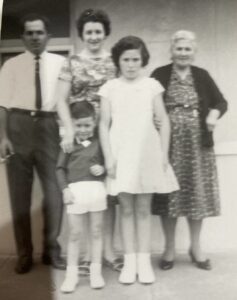

The photo above shows the Santin family, Caselle di Altivole, 1973.

Front: Diana, Clara, Alan, Romildo. Front: nonno Olivo Oliviero and

nonna Maria Oliviero with Lisa.

Following her mother

Diana Panazzolo nee Santin says, “My Mum loved her traditional cooking. I use her recipes all the time – baccalà, gnocchi, biscuits and of course, crostoli.”

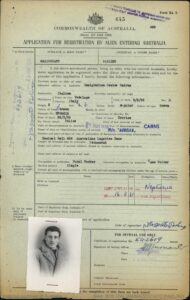

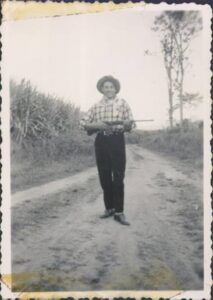

Diana grew up on Frogmore Road with her parents, Romildo (Nugget) Santin and Clara Oliviero, and her brother, Alan and sister, Lisa. Her parents worked the market gardens of 12.5 acres with Romildo’s brothers and their wives: Lui and Rosina (nee Tonellato) and Vito and Anna (nee Mattiazzo. The Santin families grew tomatoes, potatoes, cucumbers, letttuces on their land.

Romildo and Clara married in 1950 in Caselle di Altivole where Romildo had been born. After they married they lived in Adelaide at Lockleys – on the Berno brothers’ property at Valetta Road until they moved to Frogmore Road in 1952. Diana was born in 1951.

Diana was at school when she first started cooking for the family. Her mother worked in the Santin families’ market gardens and sometimes when Diana came home from school, she’d follow instructions and prepare the family meal. Diana still makes her nonna Tina’s tasty sardine dish that her children and grandchildren love to eat.

Making crostoli

Diana speaks with fondness about making crostoli which were always a special sweet food that her mother made. “It’s a thin white fried pastry, so light and crispy that when you have one, you just want more.”

Making the crostoli is now a three-generation gathering held at the home of Diana’s cousin, Sandra, and Sandra’s husband, Deni Conci. They are joined by their daughters, Amanda and Danielle and Diana’s granddaughters, Ava and Lea, and Diana’s sister, Lisa, on a date close to Christmas. Sometimes, Sandra’s sister, Denise is another cook.

It’s a big day that usually begins at 10:00 am and finishes about 4:00 or 5:00 pm.

The process of making crostoli

After mixing the dough, there are four main steps to make crostoli – rolling, cutting frying and sprinkling sugar on them. The whole process could take up to two hours. Diana takes her dough to Sandra’s home and rolls it through the pasta machine at least 12 times to make it as thin as possible.

Diana says that you have to feel the texture and make sure it is not too sticky.The thin dough is cut into strips before they are fried in a pot of oil for about 15 seconds. After taking them out, it is often the children’s task to sprinkle sugar on the crostoli.

And the recipe…

Families pass the recipe for crostoli down to daughters although it is often adapted by the next generation. Diana has modified her mother’s recipe by using Prosecco – and has generously shared it.

Ingredients for crostoli

- 6 eggs

- 300 mls of cream

- 1 cup of caster sugar

- Vanilla sugar or essence

- 4 cups of self-raising flour

- 1 cup of prosecco or wine

- ½ cup of melted butter

- Rind of a lemon and an orange

- Juice of one orange

- 1 liqueur glass of grappa

- Essence – anise, lemon, orange – or anise liqueur or strega

- Pinch of salt

- Plain flour to roll the dough

Easter traditions

Many years ago, Diana’s auntie, zia Giannina who lives in Caselle di Altivole sent her two moulds for making the pascal lamb at Easter. Diana makes the pascal lamb and marshmallow rabbits as part of the Easter feast for the family.

Another tradition is making the Veneto fugussa – a sweet bread made with yeast. Diana remembers that when she was in Italy in 1962, her nonna made the fugussa, put them on a cart under a tablecloth and took them to a neighbour who had a large oven and cooked them there.

Other foods that Diana cooks and that are part of her family Easter customs include baccalà made from stockfish and polenta.

Carrying on the traditions

Another tradition that Diana and her family follow is having roasted chestnuts in autumn. Diana makes brue to go with the chestnuts.

To make brue, you boil wine, sugar, cloves, chopped apple and pear, orange peel and cinnamon sticks. Once it is boiled, you set fire to the brew and the alcohol evaporates.

Diana also sometimes makes sbattuletto, a mixture of egg yolk, sugar, and marsala. This is added to black coffee as a pick-me-up.

Two of her mother’s traditions that Diana does not follow are cooking tripe and snails. When her nonna was alive, she would feed them with bran for several days, a process that “cleaned” them before cooking them. Diana’s Mum used to collect snails from the artichoke plants at Bolivar where the Santin families also had land. Then she would use the same process to clean the snails. When one of the Oliviero aunties came from Caselle to stay with her parents, she collected snails from Diana’s garden to prepare for a meal.

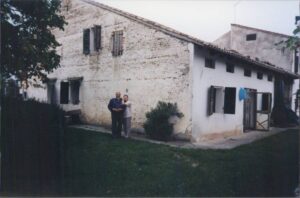

A family visit to Caselle di Altivole in 2019

Diana and her husband Roberto and two of their children and their young children visited Caselle di Altivole. Diana and Roberto stayed with one of Diana’s auntie and enjoyed spending time with relatives and renewing their knowledge of the area. Roberto’s family came San Vito di Altivole, about 6 kilometres from Caselle. Diana feels very close to her two aunties there – she says “they’re part of the connection to my Mum.”

Pride in the family food traditions

Diana loves passing on her food traditions to her family. Her daughter and granddaughters, Ava and Lea have learned how to make gnocchi and biscuits.

Diana says, “I think my parents would be very proud that we carry on the traditions. I’m very proud of my daughter, Amanda, who is also cooking lots of her nonna’s recipes.”

Diana Panazzolo nee Santin and Madeleine Regan

10 September 2023

All photos provided by Diana.