Irene Zampin, guest blogger, reflects on her family history and migration. Irene was born in Adelaide and when she was 15 years old her parents returned to live in Italy.

Reason for researching the Zampin family

The idea came to my mind two years ago when I was putting some photos of my family into frames to put on the wall. I saw that I didn’t have any photos of my father’s parents and I did not know their names. I was surprised and started to research through my cousin, Roberto Zampin.

My cousin had started researching because he was curious to know the origins of the Zampin family and he came to the conclusion that all the Zampin’s came from Pagnano (Asolo). Through the town hall he was able to find a document about the Zampinus family written in Latin dated 1545.

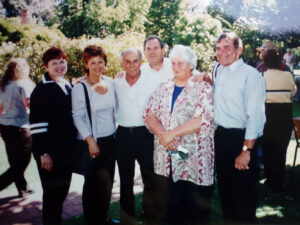

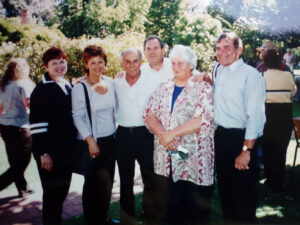

L-R: Angelo, Pietro, Rita, Antonio (Nico), Irene’s father

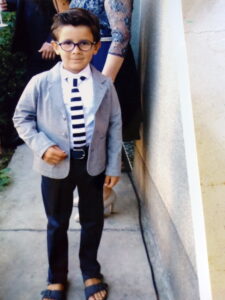

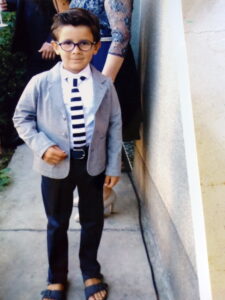

Another incident made me think about my family history. Not long ago my son brought his first photo album and showed me the family tree which had all the names of our family except my father’s parents since at that time I didn’t know them. My son was surprised that I did not know and because I have worked with my cousin on the family history, I am happy that I have the names.

I hope that my research into the family history will be useful to my children and grandchildren besides having helped me.

Importance of knowing the history of migration in a family

It’s important to understand why people have to emigrate. Their stories give us an idea of how lucky we are if we have not had to go abroad for work or to find enough food to satisfy hunger. Migrants leave their country, traditions and families because they have the need. If we know the reasons why people leave it should help us not to find fault with them or criticise them.

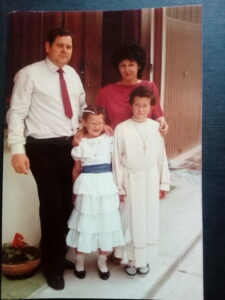

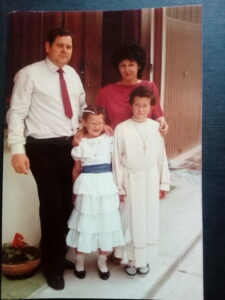

Family photos

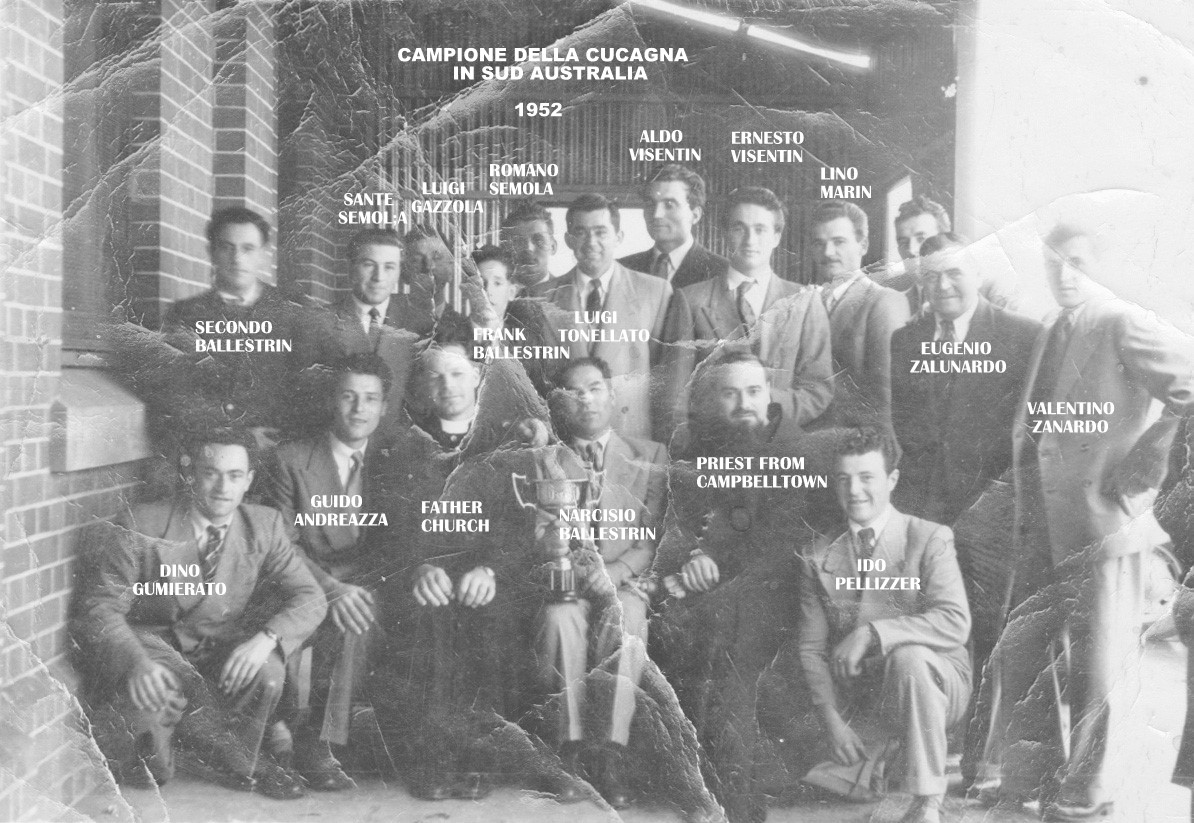

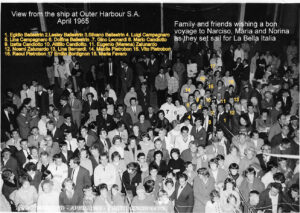

I think family photos are very important because if we had not had them, I probably would not have started researching my family. When I look at photos on the website, I am reminded of lots of people I knew when I was growing up in Adelaide and the times we spent together.

Why my father emigrated

I always knew why my parents migrated but when they returned to Italy, I was rather young and couldn’t understand why they wanted to come back when life for me, was better there. Certainly, it was not better for my father.

My father emigrated because he was poor and he was sponsored by his brother in Australia. Here in Italy there was no work and he had a family to maintain. They used to laugh about their experience in Australia; rain coming into their tin houses, their use of English and why the Australians could not understand them.

Involvement in the oral history interviews

In 2018 when I asked my Auntie Gilda and Gabriella Antonini if they would like to record an interview for the website, I wasn’t quite sure they would agree. But to my surprise, both of them said yes immediately. I was enthusiastic about the idea and I wanted to hear their stories and I knew I could help with translating in the interview.

Role of the website

The website is a great help. It was been most interesting to listen to some interviews and read transcripts and see photos of people I have forgotten. Their adventures reminded me how hard it was even for my parents. When my cousin was researching the Internet, he wrote the Zampin surname and he immediately found a link to the Veneto market gardeners website and he was happy to see all his relatives in Australia.

Irene Zampin

9 August 2020

Irene Zampin riflette sulla storia della sua famiglia e sull’immigrazione

Motivo della ricerca sulla famiglia Zampin

L’idea mi venne due anni fa quando incorniciando alcune foto della mia famiglia da appendere al muro, mi accorsi che non avevo alcuna foto dei miei nonni paterni e che non conoscevo neppure i loro nomi. Rimasi sorpresa e così ho iniziato una ricerca tramite mio cugino, Roberto Zampin.

Roberto iniziò la ricerca curioso di conoscere le origini della famiglia Zampin e venne alla conclusione che tutti gli “Zampin” provenivano da Pagnano di Asolo. Tramite il municipio è stato in grado di trovare un documento riguardante la famiglia”Zampinus” scritta in latino e datato 1545.

L-R: Angelo, Pietro, Rita, Antonio Nico)

Un altro episodio mi ha fatto pensare sulla storia della mia famiglia: non molto tempo fa mio figlio, Luca, mi portò il suo primo album fotografico dove c’era il disegno di un albero genealogico con tutti i nomi della nostra famiglia eccetto quelli dei bisnonni materni Zampin. Non erano stati inseriti poiché allora non conoscevo i nomi. Mio figlio era sorpreso da questo fatto e fu così che contattai mio cugino.

Oltre ad aver aiutato me, spero che la ricerca sulla storia della mia famiglia sia utile ai miei figli, Luca e Claudia, e ai miei nipoti, Tommaso e Mario.

L’importanza di conoscere la storia dell’emigrazione in una famiglia

E’ importante conoscere per quale motivo la gente emigra: le loro storie ci danno un’idea di quanto siamo stati fortunati a non farlo per lavoro o trovare cibo per saziare la fame. Gli emigranti lasciano il loro paese, le loro tradizioni e le loro famiglie per bisogno. Se solo conoscessimo il motivo per il quale la gente emigra, ciò ci aiuterebbe a non pensare a colpe o a criticare.

Foto di famiglia

Le foto di famiglia per me sono state molto importanti, perché non avendole non avrei fatto probabilmente la ricerca. Quando scorro le foto sul sito, mi ritorna in mente molta gente che conoscevo nella mia crescita ed il tempo trascorso insieme in Adelaide.

I motivi per i quali mio padre emigrò

Ho sempre saputo il motivo per il quale i miei genitori emigrarono ma ritornati in Italia, – ed ero abbastanza giovane – non capivo la volontà di tornare, quando la vita era lì, per me, ed era migliore. Certamente non era migliore per mio padre.

Mio papà emigrò per povertà, aiutato con la sponsorizzazione di suo fratello già in Australia. In quel tempo, in Italia non c’era lavoro e lui aveva una famiglia da mantenere e qui ridevano quando pensavano alla loro esperienza in Australia: la pioggia che entrava dal tetto di lamiera della loro casa, il loro modo di parlare l’inglese ed il motivo per il quale gli australiani non capivano la loro parlata…

Coinvolgimento nelle interviste orali

Nel 2018, quando chiesi a mia Zia Gilda (Simeoni) e alla mia amica Gabriella Antonini, se fossero d’accordo nel registrare un’intervista per il sito, non ero abbastanza sicura che avrebbero aderito. Ma, a mia sorpresa, entrambe risposero immediatamente di sì. Ero entusiasta dell’idea e volevo sentire le loro storie, sapendo di aiutarle con la traduzione delI’intervista.

Il ruolo del sito

Il sito è di grande aiuto. E’ stato molto interessante ascoltare alcune interviste e leggere le trascrizioni, vedere le foto di gente che avevo quasi dimenticato. Le loro avventure mi ricordavano quanto fossero difficili anche per i miei genitori.

Quando mio cugino fece la ricerca in internet e scrisse il cognome “Zampin”, immediatamente trovò un riferimento e un aggancio al sito del Veneto market gardeners, e felice di vedere i suoi parenti in Australia.

Irene Zampin

il 8 agosto 2020