Guest blogger, Alessia Basso, writes about her family’s strong connections to the Veneto Club in Adelaide from the first seeds that were planted in the early 1970s.

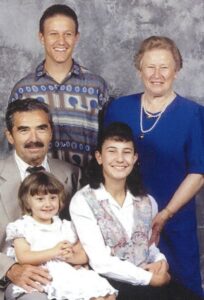

The image above shows Francesco and Lucia Battistello in front with their daughter, Marisa and son-in-law, Bruno Basso, Adelaide 1993.

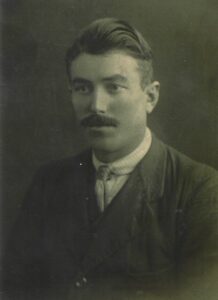

My family’s connection to the Veneto Club in Adelaide began in 1924 when my bis-nonno (or great grandfather) Stefano Battistello arrived in Melbourne, Australia. That year, my nonno, Francesco who was the youngest of four sons, was just nine months old and his father began working in country Victoria as a stonemason.

He experienced the harsh conditions of the Great Depression after his work ‘dried up’ and he walked from Melbourne to Adelaide in search of work. Bis-nonno carried all his belongings in a cart and along the way, he worked on farms for food and lodging. Earlier, he had saved enough money for deposit on a farm but unfortunately, he couldn’t keep making the repayments. He returned to Italy when my nonno Francesco was approximately 10 years old. In those times, there were no assisted passages and the fares were very expensive.

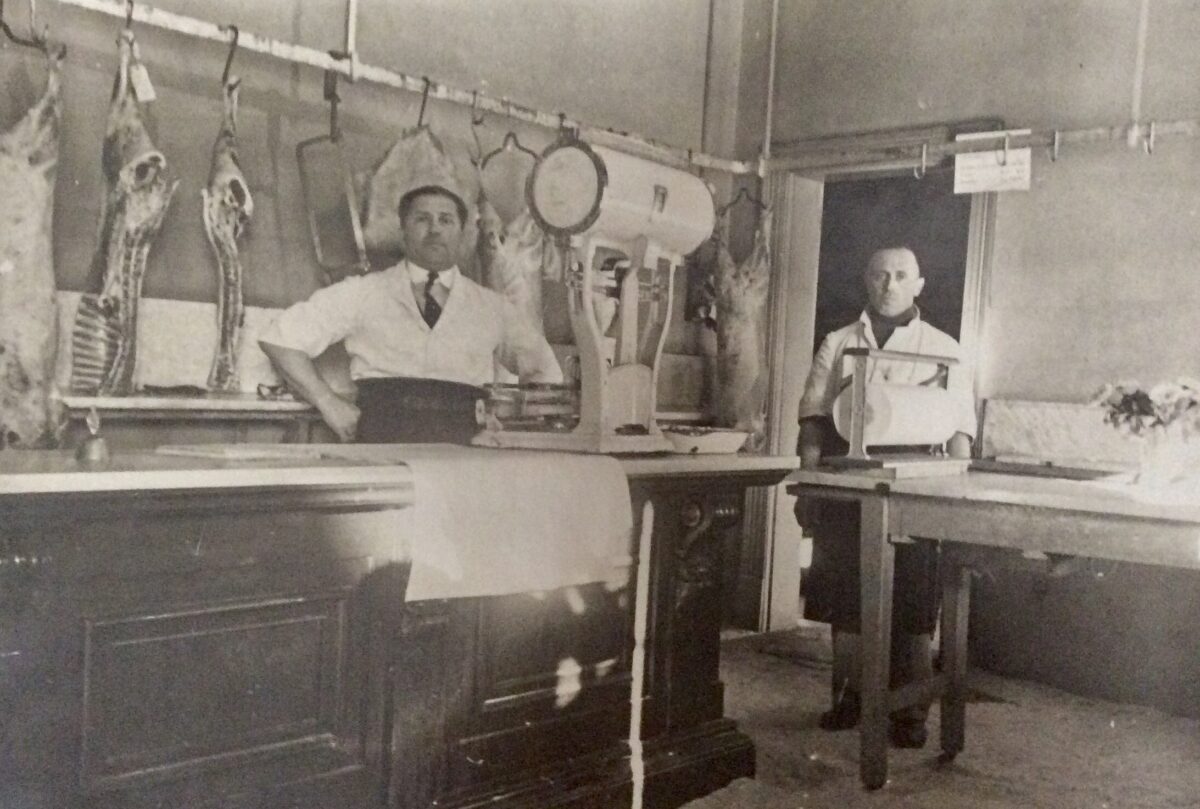

My nonno Francesco Battistello

Following WW2 and hardened by his experiences as a young soldier and later partigano, there was a lot of poverty and hardship in Italy, he needed to search for work and a better life and more opportunities for his young family. He had married my nonna Lucia Canalia in April 1948 and their daughter, Marisa, was born in October 1950. (The year before, they had lost their son Franco Pietro to meningitis.)

In June 1951, Francesco embarked on the ‘Ugolino Vivaldi’ and the journey to Australia took 3 months. He was sponsored by Pietro Franzon, a plasterer, who was married to my nonno’s cousin, Rita Nicoli. When he first arrived, he lived in a boarding house run by Flora Maschio’s parents behind the Newmarket hotel on North Terrace in the City of Adelaide.

My nonno initially worked as a carpenter for Fricker Brothers Construction. He knew that in order to progress he needed to be able to communicate with others, so he would attend English lessons one night a week at St Mary’s Convent in Franklin Street run by the Dominican nuns. He also supplemented his day job by washing dishes at Allegro’s Restaurant on other evenings. On Sundays he did weeding in an onion block in Richmond and a friend would lend him their bicycle to get there. From 1956 he had his own construction company F. Battistello & Co Pty Ltd, until he retired in 1985.

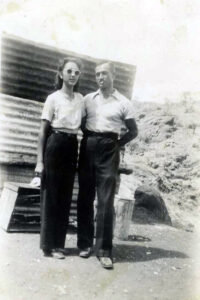

The Battistello family in Adelaide

My nonna, aged 32, and my mother aged 22 months, arrived in 1952 with my nonno’s sister-in-law to be who was engaged to Zio Virginio Battistello, nonno’s brother. My mother, Marisa Basso (nee Battistello), lived at Woodville West and attended Our Lady Queen of Peace and Star of the Sea for Primary Schooling and continued her studies at St Aloysius College for high school.

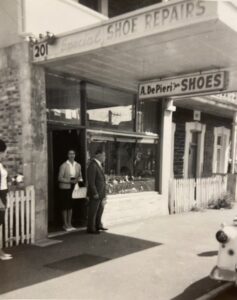

The Veneto Club Adelaide

There weren’t any clubs in the western suburbs for the young Veneto migrants to meet up and socialise together. They used to attend the Fogolar-Furlan Club in Felixstow but they wanted a local Italian club. Italians weren’t accepted/welcomed in “Australian” pubs/bars. The Veneto people in my nonno’s generation who had arrived after the war wanted a place where they could gather and connect with their fellow Veneti – they wanted a place that could be a refuge.

My nonno, Francesco, was one of the Veneto men who began planning for the Club in the early 1970s. After considerable searches for a suitable location Club in the western suburbs an abandoned clay pit that had supplied local brick works and had also been a dump became the site for the Veneto Club.

Nonno was one of four men who were guarantors for the purchase of five acres at Beverley. The others were Leo Conci, Arturo Pagliaro and Gino Torresan who made it possible to negotiate with the bank to get a loan. Nonno became the first Vice-President of the Club.

Nonno participated in the Club’s activities and it quickly became a place that drew the Veneti; it was a safe and enjoyable place to spend time with paesani.

Before the Club was opened in 1974, my nonno played Bocce in Romano Dametto’s backyard at Seaton but later, the Bocce courts at the Club made it possible for extensive competitions. Nonno played cards or Mora Giapponese on Friday nights. On Sunday nights my nonni attended Dinner Dances and the Club became a venue for special events and functions. It was very popular and apparently up to 500 people attended New Year’s Eve dinners.

My parents, Marisa and Bruno Basso, were the first young couple to have their wedding reception at the Club in 1975. (The Club’s kitchen wasn’t operational at the time so an external caterer was organised for the event).

My nonna volunteered as a cook for about seven or eight years when she was in her 60s until the paid cook took over the kitchen. My zia Mariola Canalia (nee Gallio) later became one of the official cooks at the Veneto Club.

My nonno Francesco died in 2008 and my nonna Lucia died in 2022.

My memories of the Veneto Club at Beverley

I remember Sunday dinner dances – I used to love watching the ballroom dancers. Whenever visitors from Italy came to stay with us, we’d attend at least once to show them ‘our’ piece of Italy. Family celebrations like First Holy Communion meals were held there. Christmas was a special time for children and one year Santa arrived in a helicopter! In later years there were soccer teams and Italian language classes for children.

I became a waitress one New Year Eve’s celebration and then stayed on the roster. I loved listening to the women and their lively chiaccierate [conversation]. I remember older women there like Bertina Burato, Norris Schevenin, Anna Simionato and Renata Pietrobon.

I really LOVED it – it was a weekly dose of Italian. I enjoyed interacting with the customers. They’d always ask: “Whose grand-daughter are you?” Working there reminded me of my nonni. I got to know different people and they liked sitting on certain tables. For example, Mrs Fritz and Mirella Mancini were at Table 9, Visentin/ Didone on Table 21 and Mary Dal Santo, Table 4 etc.

Joining the Next Gen Committee

In 2015 I joined the Committee of ‘younger’ people as a way of continuing the work of nonno and my Dad in building up the Veneto Club over the years. They were both acknowledged for their contribution to the development of the Club and made Life Members. I also have the opportunity to give back to the community. We organise events that are relevant and appealing to the ‘younger or third generation of Veneti’ where possible. We have pasta night and tombola, wine tasting and movie afternoons. We have also organised cooking demonstrations and workshops to pass on food traditions – gnocchi, frittole and crostoli.

In November last year we joined forces with Fogolar Furlan for Italian Week – “Italian Cuisine with Altitude,” which was very successful.

The Veneto Club today

I like to think of the Veneto Club as a kind of piazza – a meeting/gathering place for people of Veneto background – a place to remember our heritage. Unfortunately, membership numbers are declining because Italians have assimilated ‘too well’ into Australian culture. I think the provinces need to work together to support each other and we also need to collaborate with other Italian cultural clubs and support them.

The Veneto Club celebrates its 50th Anniversary in May, 2024 – a significant achievement. We hope to see the Club continue for another 50 years!

Alessia Basso

21 April 2024

Family photos supplied by the Basso family.