In this blog, guest writers, Aida, Gino and Mary Innocente continue to describe the processes of making the salami.

(The words in italics denote the Veneto dialect (v) or Italian name).

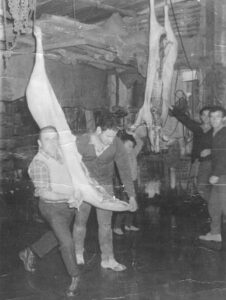

Salami-making occurred over a weekend. Usually the pig carcass was collected from the farm on Saturday and hung in the shed till Sunday, when the actual making occurred.

The salami-maker/pork butcher was key and king. We referred to him as the becher (v pronounced bekar). This is the Veneto for butcher. He was busy every weekend in autumn. Once you found a becher, you did your best not to let him go! Leandro Bortoletto, Carlo Facchin, Siro Dal Zotto and ‘Schenna’ Ballestrin were amongst the pork butchers we used. They were not butchers, but they had learnt the specialised craft of making salamis in Italy. They brought all the equipment. The mincing machine (only motorised in the mid-sixties), knives, the working table were part of the deal.

The day started at 6 am. The becher carved up the meat, selecting the meat to be minced for the salamis and sopresse, the fillet for the capocollo and bacon for the pancetta, putting aside the skin for the cotechino (sausage made of pork, lard, pork rind which requires cooking), the sausage meat, the lard and prepping everyone’s favourites, the costesine (v) ribs.

Three or four men worked with the becher. The women also worked. They fed the meat into the mincer. Mary was responsible for providing hot water, stoking the fire for the copper boiler all day. After the salamis were piped into the casings they were run through hot water, so the supply of hot water was important.

Salting the meat was crucial. Interestingly the becher did not salt the meat as this was considered an individual preference. In our family the task fell to Gino! This made his day extremely stressful as it was his responsibility to weigh all the meat prior to mincing then add the salt at 2.5% of the total weight. Sausages had slightly less salt and the cotechino, that is boiled for 3 hours, had 3% salt. The meat for mincing was weighed in bucket-loads using a pocket balance that Gino still has.

Once the meat was minced and the seasoning added and kneaded through the meat thoroughly by hand by the becher and his helpers, it was time for meranda – breakfast! Elsa was responsible for the meals and snacks. For merenda she always made Zuppa di Trippa (tripe soup) and then the costesine and small bistecche (steaks), fresh from the pig, were barbecued. Friends and paesani were invited to merenda. There was a lot of chat and laughter. It was a celebratory meal.

After merenda, the actual making occurred.

The becher was responsible for packing the mince evenly into the casings. It was important that the packing was not too firm as in the process, the salamis could burst. The mince would be threaded into the casings and then the becher held the salami under water and squeezed as much as possible, releasing excess moisture. The salamis were then pricked. String was wound at both ends of the salami, to hold it tight. The becher held the string in his mouth, biting it when he needed to tighten the knot. In time he wore a string feeder around his neck. Saving lots of harm to his teeth!

The becher would also string the capocollo and pancetta before and after they were encased in bungs. Later elastic netting was used.

Much folklore surrounded salami-making. Dates were set for when the moon was waning; menstruating women were not permitted to help as their condition might spoil the salamis. In Italy a prank was played on the unsuspecting (usually children or the naive) to go seek the mould for the martondee (v), a hamburger like pattie encased in stomach lining. In on the joke, neighbours would hand over a bag full of weights to take back to the becher!

Keeping the becher happy on the day was a big priority. He was waited on hand and foot. Drinking wouldn’t start first thing but not much later, remembers Gino. The becher would say sti saadi i xe suti (v) “These salamis are dry.” It was clear what he meant!

At the end of the day the salamis were hung from rafters in the shed where they remained until they were dry, a period of 4-6 weeks. After that they were hung in the cellar where they remained until eaten.

And what was the best part of making salamis? Eating them of course!

Aida, Gino and Mary Innocente

16 May 2021

Photo courtesy Wikipedia: State Car 4 Royal Tour 1927.

Photo courtesy Wikipedia: State Car 4 Royal Tour 1927.